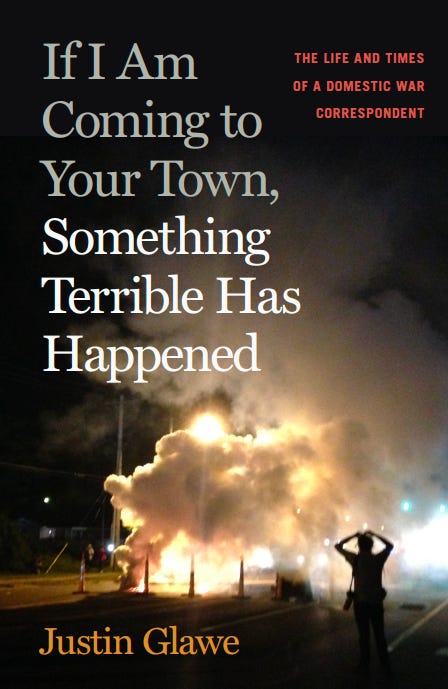

Less of a news thing today and more of something that you’ll want to sit down with a cup of coffee for. The University of Georgia Press has completed design on the cover for my forthcoming book, and I’m very excited to share it with you today. Below is an excerpt from the book. If you support my journalism and writing, please consider a paid subscription to American Doom or a contribution. Founding members will get a signed copy of the book, called If I Am Coming to Your Town, Something Terrible Has Happened - The Life and Times of a Domestic War Correspondent.

As far as domestic conflict zones go, this one was pretty tame. The Georgia State Troopers who were blocking access to part of the Hyundai Metaplant last week let me drive right on by into an area that looked like it was meant for employees only.

On the main road leading into the plant no one bothered the small group of us press who had gathered there. The helicopter flew overhead at a distance. Inside, what I imagine were dozens of armed immigration agents rounded up terrified workers, including a pregnant woman, eventually arresting more than 400 of them. A Republican political candidate took credit for the raid, providing more evidence that if armed authoritarian forces don’t get you, your neighbors just might.

I left this troubling scene and drove to meet a contractor at our new home. There I discussed the gates to a white picket fence we’ll have constructed to keep the dogs in the yard, fixing minor termite damage, running some new electrical, and when the permits will be secured. In other words, normal, everyday life stuff.

This juxtaposition between the worlds I inhabit as a journalist and a citizen, husband, and otherwise normal guy, are jarring at times. I flew to Los Angeles in June to witness an illegal domestic military deployment and the ensuing police riot. A few days later I was back at home, mowing the lawn.

Over the years, I’ve learned to balance these two opposing versions of reality, but it’s taken a lot of work and some pain to get here. For a while, the everyday niceties of life — this semi-suburban reality I often find myself in now as I come into middle age — were difficult for me to cope with. How could I partake in, let alone enjoy these things, knowing that flames, violence and strife were ravaging some city just a quick plane flight away?

I rebelled at the thought of doing anything other than concentrating on conflict and chaos; you go have your nice things, I would think of others with derision. I’ll stay here in the dirt.

Now, I’m much better at maintaining a balanced perspective — one that reminds me, for every ugly and violent thing, there is a beautiful and peaceful one.

This should come in handy over the next few months and years, because even as I’ve achieved this greater sense of balance and acceptance, things have gotten worse.

As a nation, we are hurtling toward a version of government and society that is brutal and punishing. This violence and vindictiveness has always been just under the surface of American life — the subject of most of my reporting throughout my career — but is now emerging in the open, as the official policy and characteristic of not just elected officials and the governments they control, but of our friends, neighbors and families.

Now, I’m faced with a new juxtaposition to come to terms with: that even as my personal life gets better, more loving, more peaceful, more stable, the collective American life continues to decline into conflict and instability.

I am very lucky to be able to leave a situation like the Hyundai raid and return to my comfortable, stable personal life. Many others are not. I’m also very lucky to be able to make a living doing what I love, and to be able to express my opinions and have a voice while so many are increasingly constrained from doing so.

Coming to terms with this injustice — that for a variety of reasons that include privilege, circumstance and luck, I am able to travel freely between the theaters of conflict and peace — has taken a long time. It’s one of the themes of my forthcoming book, which will be published next year by the University of Georgia Press — another thing in my life for which I consider myself very lucky.

In February, on the first anniversary of this publication, I shared an excerpt from my book, which is called If I Am Coming to Your Town, Something Terrible Has Happened - The Life and Times of a Domestic War Correspondent. Below is another excerpt. I hope you’ll read it and think about all the things in your own life that you’re grateful for. Because in the face of brutality and oppression, we all need reminders of gratitude and hope.

***

PEORIA, Ill. — On a hot July morning with the sun beating down on the dirty dashboard of one of the newspaper’s cheap Dodges, I was driving on a street on top of the west bluff that separates a part of Black Peoria from white Peoria when I heard the call on the police scanner. “10-32,” and then the address. “10-32” means someone has been shot. The address I knew, more or less: an ice cream shop called Tall Bob’s in the South End of Peoria. I got there before the police had crime scene tape up. A man had been shot somewhere else before he ended up in the parking lot where he screamed as the paramedics tried to stop the blood from running down his leg. The blood ran down the side of the tan leather seat of the SUV and dripped onto the door jamb. I watched the man bleed and scream as the paramedics around him tried to stop him from doing both. Fifteen minutes before I stood there in the parking lot I had left the newsroom for my first full shift on the cops beat. This was my first morning on the job. By the time I stopped to look away from the bleeding man I realized I was on the other side of that tape. I remember a cop saying that I’d have to stay now that I was on that wrong side of the line. But he was just joking so I left and drove down the street to where the police were having a press conference where they explained what had happened. When the police and the paramedics had finished their jobs and left, there were bloody plastic surgical gloves strewn all over the parking lot where people waited in line for ice cream like nothing had happened. Tall Bob’s was open for business again.

It was 2012 and I was a cub reporter. Technically, I was an intern but I worked 40 hours a week just like everyone else at the paper. The newspaper’s headquarters sat on the edge of the east bluff, which overlooked the river on a road called 1 News Plaza. The bluffs, as they had since Peoria was founded, were natural markers between the Black and white neighborhoods of the city, between poor and rich. The paper’s printing press took up an entire building with three stories of glass windows that lit up the giant printing press inside like a snow globe at night. Toward the river from the press room was the main entrance, where in neon red gothic font the words Peoria Journal Star shone across the parking lot. I never saw anyone in the lobby but I walked through it each day and nodded at a secretary who is no longer there because no one is there anymore. up a stairwell with seafoam green tiles on the wall was the hallway that led either to the executive suites or past advertising and photography. I always chose the path past advertising because it meant I didn’t have to walk by the editors’ offices. I was scared of them and thought it was only a matter of time before they figured out I didn’t belong there and fired me.

Six and sometimes seven days a week I walked into the newsroom through the back entrance by the photography room and passed a cork board that was supposed to be for upcoming events — fundraisers, happy hours, birthday parties — but never seemed to have anything current on it. Next to letters mailed to the newsroom from reporters who had left the paper behind was a photograph taken less than a decade before. It showed more than 100 people all standing under the gothic font of the newspaper’s entrance smiling on a blue sky day. More than half of their faces were covered with red Xs. Some quit, some took buyouts or were laid off as different owners of the paper looked to cut costs. The newsroom was filled with empty desks that once belonged to these departed reporters. The reporters who were left just kept working next to the empty desks, absorbing them into their own workspaces and filling them with whatever clutter couldn’t be contained on their own desks. Stacks of yellowing newspapers sat on the empty desks of the reporters who once put stories on those pages. I walked into the newsroom hungover and with dry mouth from the night before while sipping a cup of coffee and carrying a sub for lunch. I went to the desk where Anthony or Brad or Gary sat under a brown plastic sign hanging from the ceiling that said “Metro City Desk” and grabbed a chunky, black police scanner.

When something bad happens the scanner plays the all clear tone, a high-pitched boooooooooooooop followed by a click. When the scanner hears a voice, it stops on that frequency and plays the sounds back to you. Then the information comes in from the dispatcher or an out-of-breath cop: a person shot, an armed robbery, police opening fire. After the all clear tone I waited to hear the address. “10–32, 600 block West Main.” Once I heard it I’d grab the scanner and a notepad and drive to the scene. There were a lot of them in the summer of 2011. That year, Peoria had the most homicides in a year since 1989. Twenty-three people were killed, including a five-year-old boy who took a bullet that went through his bedroom wall when he was at his uncle’s house for a sleepover. The cops thought whoever killed the kid was actually trying to kill the uncle but the uncle never cooperated with police and so they never solved the child’s murder.

Boooooooooooooop the scanner would say and I’d perk up. Even today, I can hear that all clear tone when its musical key plays in some commercial or on someone’s phone over the din of any barroom or the whine of any highway. It comes back to me at times when I’m least expecting it and puts me right back in that newsroom or driving around the streets of Peoria.

I heard the all clear tone one day and listened for the address, then drove toward Trewyn School in the South End. There was a car with the doors open and little yellow placards with numbers on the ground where the shell casings had fallen. There was a 19-year-old boy under a white sheet. Neighbors came out of their houses to see what was going on and people driving by stopped to get a look. A woman called out to anyone who would listen that if all these kids in the neighborhood were so good with guns that they should “go to Iraq” and fight in the war there. A police lieutenant hugged her by promising to find her son’s killer. She landed on her knees and cried and begged God to bring her son back but there was no answer.

I drove back to the newsroom and wrote up the story which went under the headline 1 DIES IN SHOOTING. That story got the front page because it happened in the daytime when a photographer was able to get to the scene and take a photo. You need a photo if a story is going to go on the front page. Most of the stories I wrote about people who were killed in Peoria didn’t end up on the front page. Instead, I wrote them up in a few paragraphs called a brief. The brief would say when and where the person had been killed but not much else. The briefs went on the inside of the paper in the B section, where only those who knew where to look could find them.

About a month later I walked into the newsroom to find a note on my desk. A 23-year-old man named Robreco King was found dead the night before in an empty lot in the South End, where a lot of the city’s crime and most of its murders took place. I called the coroner and asked for the man’s home address, which she wasn’t supposed to give out but did so under an unspoken agreement with the paper.

I knocked on the screen door to a small screened-in porch and told a woman who I was. Then an old man came out and invited me to sit down with him in the porch. He was the victim’s grandfather, he said. His son, the dead man’s father, fiddled with a car parked in the driveway but didn’t want to talk. Besides, the father couldn’t hear very well because he had been shot himself years before and the injuries had taken some of his hearing. But the grandfather wanted to talk. He was frail but wiry and strong in the way that old men, insistent upon continuing to live, are. What a meaningless thing, to take a life, he said, more upset than sad. He knew. He had done it before and paid the price with a long prison sentence for a killing he did decades earlier in Chicago. After that he’d come to Peoria to get away from the violent madness of the big city, only to find a different variant here. His son had almost been killed in the shooting that partially deafened him, and now his grandson was dead. He just wanted the cycle to stop. “I wish someone would make these people put it on paper: What do you get out of killing another man? People don’t put value on life, but it’s worth a whole bunch.”

I called my editor and told him this incredible story: a reformed murderer whose son was almost killed and now had a dead grandson, and who was calling for peace on the streets of Peoria. So we sent a photographer. The grandfather sat on the couch with his daughter-in-law and her children and posed for the photo. The photographer and I thought we had done something powerful: humanize a murder victim and his family as something more than just another “Black man killed in Peoria’s violent South End.” The next day, I opened my email to find that I had missed what the Journal Star’s readers had not: the grandfather’s fly was open. He had bared his soul for all of Peoria to see but all that the readers saw was that he had forgotten to zip up his pants.

***

After a few months at the paper, the editors asked me what cops shifts I wanted. I chose nights because that’s when the most action was. But no matter how big of a night I was expecting — maybe a revenge killing after a week of violence in a certain neighborhood — I always had to write a feature to fill the front page. Splitting your time between writing fluff stories about Oktoberfest or the opening of a new Bass Pro Shop and standing around at crime scenes is a fucked up exercise in understanding the ubiquity of violence in American life. It’s everywhere and nowhere at the same time. It is hard to enjoy a dinner party when you know that someone is being murdered just across town and you’ll have to write about it. On nights when I wasn’t working I was usually listening to the scanner anyway. If I wasn’t listening, I was usually distracted, keyed up, unable to concentrate on whatever was happening around me because I was thinking about what I was missing out on the streets. I call this straight life and real life. Straight life is what most of us do all day every day. We pretend everything is fine as we buy houses and clean our cars, plan dinners and happy hours with friends, go to see bands or play in a softball league. Real life is what happens when the sun goes down and someone pulls out a gun.

I started to spend less time in the straight life. Instead of going home after work I went to the bars downtown and sat in back booths alone and watched people pass by, knowing nothing of what had happened in the city that day or what would happen that night. But I knew Peoria as if it were a person and I could read her face. When fall is coming and gray skies hang over the city for weeks, the city’s abandoned homes stick out a little more. When summer is peaking and everyone’s grass is green and you can hear lawnmowers and sprinklers and kids giggling as they play in the streets, Peoria seems as good as any place. But nighttime is different. Sometimes daytime is different, too. It just depends on the time of year, or how much someone has had to drink, or nothing at all. Sometimes people kill just because they feel like it.

***

There is one very quick and simple way to tell that the past sins of this country were never really addressed, and that’s by taking a trip to any given courthouse on any given day. In Peoria, the white lawyers and judges constantly doled out sentences and judgment to the city’s poor Black residents. The dockets there were filled with Jacksons, Kings, and Hightowers; in Bemidji, Minnesota, last names like Whitefeather and Kingbird filled court filings.

I could see dozens of little lights from the fish houses out on the frozen lake as I drove into town on a freezing December night. It took 12 hours of driving to get from Peoria to Bemidji, where I had landed a job as a reporter at the Pioneer. Bemidji was in the middle of a trio of reservations: White Earth to the west, Leech Lake to the east, and Red Lake to the north. Like a lot of cities, even small ones, Bemidji is racially segregated, with most of the Natives living on reservations and coming to town mostly to work and to go to court.

I made a spreadsheet of cases I wanted to write about. There were killings, stabbings, and sex crimes in this little town that hadn’t gotten much attention in the Pioneer before I got there. I had taken the job because the Journal Star. had no place for me. After working as an intern for more than a year, I interviewed for an open reporter position. One editor told me she was concerned about my lack of a college degree. I had made the mistake of thinking that the words I was putting into the paper themselves were worth more than a degree from some school.

After weeks of sending résumés and clips to newspapers around the country, the Pioneer was the only one that took my call. It helped that a friend from Minnesota who had interned in Peoria had taken a job there to cover City Hall. He got my foot in the door. I worried that there wouldn’t be enough bad news in the small town for someone like me to cover. An editor in Peoria told me that there were stories to be told everywhere, and sometimes the small places had plenty of ugly things going on.

I didn’t trust the cops or the people in the courthouse and they didn’t trust me. Not long after I got to the paper, a longtime sports reporter at the Pioneer told me that I would attract more flies with honey than vinegar because I was making some people in town angry with my style. They thought I was a hard-charging city slicker or something like that. I was and I was fine with it. As far as I was concerned, vinegar was the only thing that could get the job done. The newsroom was clean, new and comfortable and smelled like carpet glue and fresh paint. The people who worked there were all from the area and had worked there for years and probably had never seen a body under a white sheet. I was convinced something was wrong with this town and that I was going to find out what it was. I began my search by pissing off the police.

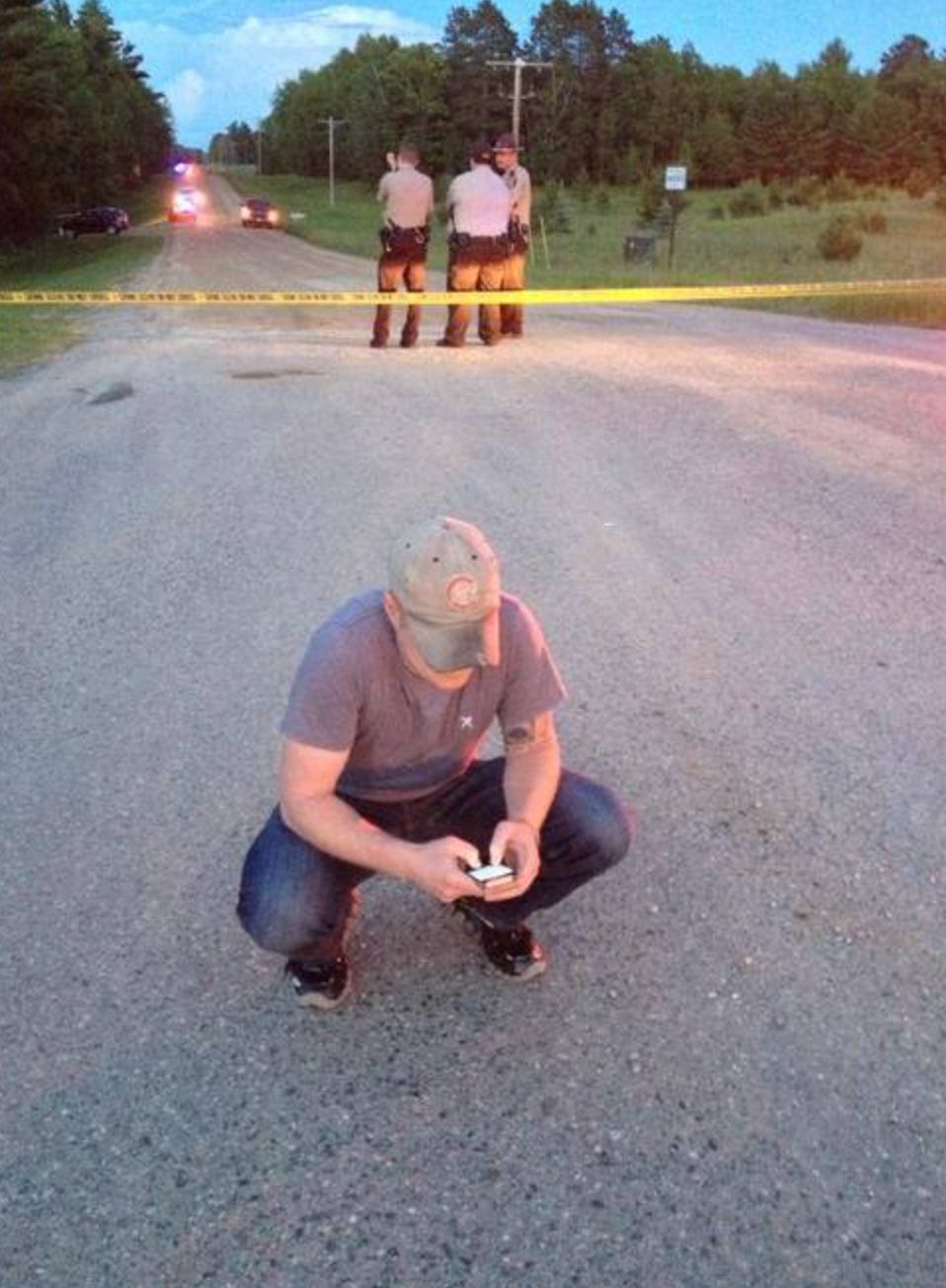

The cops had killed an Iraq war veteran in his own home during a nighttime standoff. I put the veteran’s widow on the front page with her questions about why police had killed him. Six months later a SWAT team sniper killed another man after an hours-long standoff at his home. I spent the day standing down the road from the man’s home while listening to police chatter on my scanner. I also put out some of the information I heard from the scanner on Twitter. After almost five hours, the standoff ended with a helicopter taking the man’s body to Fargo for an autopsy. The next morning, the sheriff and the police chief came to the Pioneer newsroom and sat in a small conference room with the editor, telling him that I shouldn’t have posted information about the standoff online. They said that I could have put officers in jeopardy and compromised the entire operation. I had a hard time believing that the subject of the standoff was following my Twitter account for updates when he could have simply listened to the same police radio frequencies I was. I also had a few questions about why police had to kill the man. They said it was because he pointed a rifle at them. I think the cops just got tired of standing around in the sun all day and wanted to go home — a thought I did not share with the two law enforcement veterans staring me down in a conference room at the newspaper.

Then, a few days later, I reported the name of the officer who fired the fatal shot. In Peoria I had been taught that the profound responsibility society gives to police officers to take a life means that we get to know their names when they do. The town’s two top cops didn’t see it that way. They refused to release the names of the officers involved, so I went around the sheriff and the chief of police and got the names from the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension. I called a reporter in Peoria for a gut check and he confirmed my thoughts — it’s that simple, he said. Cops kill someone, you print their name. I didn’t think much of it. I did my job and went about my day, not knowing what would happen next.

The newsroom was flooded with letters and emails to the editor and publisher deriding the paper for its decision to publish the officer’s name. In Peoria, this would have been no big deal. It was a city, and everyone there played by the rules of a city. There was an expectation that if you did something newsworthy — whether you were a teacher who had molested students or a cop who justifiably killed an armed madman — your name would end up in the paper. But before I’d arrived in Bemidji, this apparently wasn’t always the case.

Plus, I’d learned something else, something that would come back years later and continues to shape the grievance-based politics of our present and future: I had made the mistake of thinking that police considered themselves responsible to their fellow citizens in the same way that I was held accountable by the people reading my stories. I thought we were all part of the same society. Instead, I learned that many police consider themselves separate from the rest of us, maligned defenders holding chaos at bay so we can enjoy cookouts in our backyard without being murdered in cold blood.

***